+

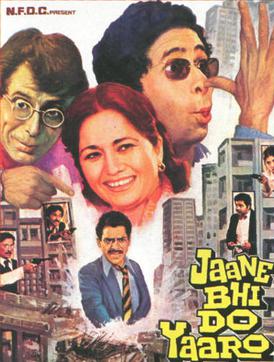

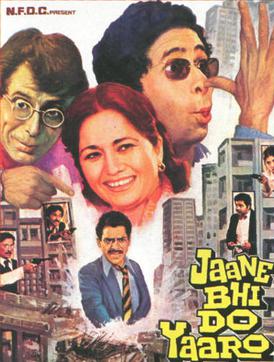

For anyone with even a nodding acquaintance with Indian cinema, Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron (1983) and Deevar (1975) evoke instant recall. If the former is the best and brightest in cinema noir, the latter is chockablock with immortal dialogues and iconic characters. Two recent books on the two films – one by an irreverent blogger and columnist and the other by a historian and academic – are a welcome addition to the growing body of work on popular culture and the role of Hindi films in shaping and defining Indian sensibility.

For the uninitiated, Jaane bhi do ... can best be described as a breathless satire of cosmopolitan India; it builds gag upon gag till the viewer finds himself atop a pyramid, one that affords a panoramic view of a malodorous society riddled with various ills. To my mind, there is nothing comparable with it in Indian cinema, certainly nothing that comes close to its off-kilter view of almost all those things that upset or anger us. The film is episodic, disjointed, even juvenile in its innocence, yet it works brilliantly and not in parts but as a whole too. In fact, so brilliantly did it work that it makes one wonder why – in this age of de rigueur sequels -- this formula of exaggerated comic situations, heightened absurdity and shooting from the hip digs was never repeated? One would have thought that the success of Jaane bhi do … would launch a comic revolution in Indian cinema. But it didn’t. I wonder why?

Looking back at the film while reading Jai Arjun Singh’s immaculately researched book, I am struck by the sheer spontaneity of the action on screen. Yet Singh’s interviews with the film’s director, lead actors and others in the ensemble cast reveal the method behind the madness and the minute attention to the smallest detail that filled the canvas on screen. In the course of several interviews with the film-maker Kundan Shah, Singh has commented on a remarkable generosity of spirit; in the posters of films by Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Tanvir Ahmad, Muzzafar Ali that have been strategically placed in various frames and in naming a park after Antonioni because a particular scene is inspired by Michaelangelo Antonioni’s Blow Up. For a film that revels in disorderliness and randomness to have these precisely placed markers, indicates order and an eye for detail apart from the generosity.

As a viewer, however, one is struck by the refreshing candour, even naiveté that comes across. There is no attempt to intellectualise the comedy; every situation, every scene seems instinctive. The humour rests on a complete suspension of disbelief; the sheer improbability of some of the more whacky scenes works to their advantage. What is also very refreshing – given the knee-jerk outrage that has become the norm rather than the exception in our part of the world – is that the film takes on several holy cows… there is a hilarious scene involving a dead body in a burqa amidst a sea of burqa-clad women; a completely OTT scene involving the body of a (Christian) policeman in a coffin and of course the Mahabharata episode which entailed a delightful spoof of the Ram Lilas we have all seen at some point in our lives. Yet I don’t remember it causing any outrage. Why was that? Surely we were not more tolerant as a nation back then? Or was it something about the film itself – its insouciance and, yes, innocence, that allowed it to take on both holy cows and ugly underbellies of cosmopolitan Indian?

But Jaane bhi do… is as much about the loss of innocence and the breaking of ideals. At the end of the day, in the film, dishonesty wins over honesty, cynicism over idealism and the system triumphs over the individual. The two main characters, played by Nasiruddin Shah and Ravi Baswani in the finest roles of their careers, set off on a bildungsroman that exposes the builder-politician-journalist mafia in all its ugliness and greed. In a landscape peopled by incompetent bunglers and willful swindlers like the smoothly menacing Tarneja, the only two good, decent, upright people – Vinod and Sudhir – end up as fall guys who end up in jail. Beneath its frothy exterior and its infra-dig humour, you begin to wonder if the movie has been hiding a black heart all along.

The movie ends with Vinod and Sudhir walking out of jail, still in their striped jail pajamas. In the backdrop the anthem, Hum honge kaamyab, hum honge kaamyab ek din, plays mournfully. Does that hint at hope rather than despair? Or, is that too a tragic-comic prop meant to raise laughs? I remember all those years ago leaving the cinema hall wondering if this was a dark film full of nihilism and despite the funny goings on? Or was the sadness filled with hope? Reading Jai Arjun Singh’s book, I find there are no easy answers.

The other book, as well as the film, Deevar, has an altogether different approach. The two books are apples and oranges in a sense. Evidently, Vinay Lal’s training as a historian governs the way he writes about cinema and popular culture in Deevar: the Footpath, the City and the Angry Young Man. Here, as in Jaane bhi do… the city of Mumbai (or Bombay as it was then called) looms large. Vinay Lal looks at the making of the film through the prism of a social historian; he has looked at issues of migration from rural areas, the problem of dockworkers and daily wage-earners, the homeless who sleep on footpaths, the smuggling dons, the rural-urban divide and the crossing-over of that divide through the upward mobility of Amitabh Bachchan’s character (called Vijay in the first of a series of films).

Lal has also used certain scenes and motifs from the film and invested them with near-mythic qualities: the tattoo on Vijay’s hand (Mera baap chor hai), the skyscraper vs. footpath image, Vijay buying the skyscraper where his mother (the inimitable Nirupa Roy) worked as a daily wager, the signature whether it is Vijay’s father’s or the one demanded by Vijay’s brother Ravi, the temple scene where an angry and atheistic Vijay confronts the deity his mother has worshipped all her life, and of course the near-mythic dialogue Mere paas maa hai in answer to Vijay’s contemptuous Mere paas gaadi, hai bangla hai, paisa hai…Tumhare paas kya hai?

Dwelling at length on the dialectic of the footpath and the skyscraper, Vinay Lal writes:

Moving as he does between the extremes, from the village to a global trade in smuggled goods, from the uniform of a mere coolie at Bombay’s docks to tailored suits, we should not be surprised that Vijay [Amitabh Bachchan] teeters between the footpath and the skyscraper. Deewaar has justly been described as a film that gives vent to the explosive anger of discontented young urban India, as well as a film that, while exploring, partly through tacit invocations to the rich mythic material found in the Mahabharata, the inexhaustible theme of fraternal conflict, provides an allegorical treatment of the eternal struggle between good and evil within oneself.

While this makes engaging reading, it does make one wonder if occasionally serious readers and interpreters of popular cinema invest more in a film than was intended in the script? Did the scriptwriters, the duo of Salim-Javed, have any of these dichotomies in mind when they were writing what was basically an intelligent, but masala, Hindi film? I wonder.